In a series of postings, we’re exploring how conscious change happens in communities. If you haven’t read the first posting in this series, please take a moment to do so.

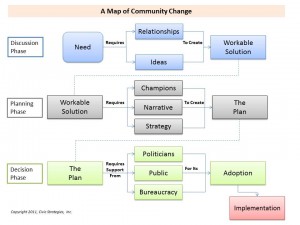

As we walk through the community change process, let’s pause and see if we can connect more closely the first two parts, the discussion phase and planning phase. Briefly, the discussion phase awakens the community to a need and pulls together a group of people to search through a number of possible answers for a workable solution. The planning phase takes the workable solution and turns it into a set of specific plans that speak to the public, decision makers, and funders. It may also involve organizational work and fundraising.

What connects these phases? Aside from you, as the primary leader, it’s the guiding coalition. This is the group that helps you, in the discussion phase, sift through possible solutions and come up with the one to take forward. In the planning phase, you still need a group—if anything, the tasks multiply and grow harder, so you need others to help carry the load. And the obvious people to begin with are those who were with you in the discussion phase. After all, by this point, it’s their project, too.

But who else is needed? As I mentioned in an earlier posting, a good way of thinking about guiding coalitions is to consider people with expertise, power, credibility, and the ability to get things done. How does this change in the planning phase? It doesn’t. It’s just that, as you work into the details, the problems and opportunities grow narrower and deeper, so you’ll need people who can help you not just with the broad outlines of community change but the crevasses as well.

To make this clearer, let’s return to the example I used in my planning phase posting, the building of New York’s High Line Park. Remember that this project began in 1999 when two neighborhood residents, Joshua David and Robert Hammond, learned that an abandoned elevated freight line running through their West Side neighborhood was to be torn down. They both had the idea that something, some kind of public space, could be made of this industrial relic and provide a much needed amenity. Thus began one of the most astonishing urban improvement projects of the past half-century, culminating in 2009 with the opening of a park in the sky, one of the country’s most innovative public spaces.

Who joined David and Hammond’s guiding coalition, and when did they join? As they write in their book, “High Line: The Inside Story of New York City’s Park in the Sky,” David and Hammond started out with little knowledge of parks, planning, politics, or charitable fundraising. So they began with what they had: friends who knew people. And, here, they were lucky. Hammond had gone to college with a man who had become a well-connected New York lawyer. He introduced David and Hammond to the first member of their guiding coalition, a developer and former political insider named Phil Aarons. Aarons had three of the four qualities a guiding coalition needs: expertise, credibility, and the ability to get things done. He was immediately won over by the idea of the High Line and invested untold hours in making introductions, attending meetings, and advising David and Hammond about politics and public opinion.

Hammond had another college friend, Gifford Miller, who was by then a city council member (he would later be president of the council). Skeptical at first—Hammond says Miller called it a “stupid idea” when he first heard it—Miller changed his mind when Hammond took him atop the High Line and he saw its potential. Miller brought credibility and expertise to the group (he knew city government and especially the city council) and, of course, power.

Others joined the coalition soon after. There was a lawyer who understood transportation law and federal regulation, and helped guide them through the federal maze. Miller brought in the city council’s zoning and land use attorney. Aarons introduced David and Hammond to Amanda Burden, who was then a member of the city planning commission. In time, Burden would become the project’s most important champion and strategist. (In a stroke of luck, when Michael Bloomberg was elected mayor, he appointed Burden the city’s planning commission chair, which is a powerful position.)

Even more joined in time. One was a city government lobbyist who knew the nooks and crannies of city hall even better than Miller and Aarons. Another city council member, Christine Quinn, came aboard. An economic development expert, John Alschuler, was hired to study the project’s impact on property values and was so taken with the High Line, he stayed on as a volunteer and became part of the inner circle. There were others: One was a man who knew so much about the neighborhoods that the project crossed that he was known as the “mayor” of the lower West Side. He helped convince building owners and neighborhood groups to support the High Line. Finally, as the project moved into major fundraising, a partner at Goldman Sachs, the Wall Street firm, joined the group to help them connect with the wealthiest families and corporate interests.

These people came as needed. Alschuler was brought into the inner circle after the workable solution had been identified and when more detailed plans were needed. The lobbyist and neighborhood “mayor” joined as the approval process, at city hall and in the neighborhood planning boards, approached. The Goldman Sachs partner arrived after the project had won its most critical approvals and its heaviest fundraising began.

Others were influential, but more as allies than members of the guiding coalition. One was Dan Doctoroff, the deputy mayor for economic development. Acting on Mayor Bloomberg’s behalf, he had major development plans for the northern end of the High Line, an area called the Far West Side. Doctroff’s support was crucial for the High Line but his own plans were controversial. So David, Hammond and the rest of the guiding coalition walked a fine line. They had to stay in Doctoroff’s good graces while not being too supportive—otherwise the neighborhoods would have turned against the High Line. Somehow they managed this well enough that when Doctoroff’s Far West Side plans fell apart, the High Line sailed ahead . . . with Doctoroff’s support.

There were other important supporters, including celebrities, business leaders, politicians, and society mavens, and they were frequently consulted. But they weren’t in the guiding coalition. Yes, they might be in the ribbon-cutting photographs or featured in videos and printed materials (that was a way of compensating them for helping out), but they didn’t map strategy or search for answers and allies. That was the work of the guiding coalition.

At a point, the High Line needed more than a loose coalition; it needed the structure of a full-blown nonprofit, which came to be called Friends of the High Line. Many of those who were in the informal guiding coalition became board members. Aarons was the first chair of the Friends of the High Line. The next was Alschuler, the economic development expert who started as a consultant and became an advocate.

The interesting dynamic about guiding coalitions is how members’ involvement waxes and wanes. That is, at a point, one person might be the key member because she has the critical expertise or credibility, but at a later point, she may not be as central to things. As long as it’s an informal coalition, these things are almost self-regulating. That is, as people feel they are needed, they step up. When they’re no longer needed as much, they drift away.

When a coalition becomes a nonprofit board, though, it takes greater management. Someone has to choose who stays on boards and who leaves. This is known as “board development,”and it is one of the most important strategic duties a nonprofit director and board chair make. And how do you choose good nonprofit board members? Well, expertise, power, credibility, and the ability to get things done are good places to start. But add one more: the ability—and willingness—to raise money.