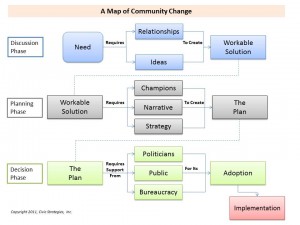

In a series of postings, we’re exploring how conscious change happens in communities. If you haven’t read the first posting in this series, please take a moment to do so.

In a time when many wonderful parks have been built, New York’s High Line may be the most wonderful of all. It’s a park that runs above the street and through buildings on Manhattan’s West Side. If you climb the stairs and walk the portions that are completed (it will eventually be a mile and a half long), you’ll see something at once modest and spectacular. The modest part is the park itself, a narrow trail edged with plants and trees with resting areas along the way. The spectacular part is the setting: a park in the sky, wending its way through post-industrial New York. The reviews, as you can see in this video, have ranged from glowing to awestruck.

But my interest is not in the park itself. It’s in the project—the road the High Line traveled from a pair of neighbors looking up and seeing potential in an old elevated track until its opening in June 2009—and what that journey tells us about the second phase of our map of community change, the planning phase.

Background: In 1999 two men, Joshua David and Robert Hammond, attended a neighborhood planning meeting on the future of the abandoned rail line known as the High Line. Some landowners wanted it torn down to make way for new developments. David and Hammond, who did not know one another, came with another idea, that you could turn this elevated freight line into . . . something else, some kind of community asset.

Their ideas were vague. They thought about a park of some sort, but what kind of park could you build on a narrow set of elevated railroad tracks? And David and Hammond hardly seemed the type to turn vague civic ideas into reality. David was a writer who specialized in travel articles for glossy magazines. Hammond was a consultant to business startups. Neither had run a nonprofit, managed a park, or had any serious contact with government at any level. They came to the meeting with hopes of volunteering for a nonprofit—any nonprofit—that would make the High Line into a community asset. What they learned was there was no such nonprofit. So, pretty much on the spot, David and Hammond decided to do it themselves.

If you’re following this on the map of community change, we’re at the very start of the discussion phase, with the recognition of a need. Or, in this case, two needs. The first was David and Hammond’s belief that, in the crowded lower West Side of Manhattan, there wasn’t nearly enough open space. That part of New York takes in many old industrial areas (one neighborhood is still called the Meatpacking District). In the late 19th and early 20th century, New York didn’t build parks in places like that.

The other need was for quick action. If somebody didn’t act soon, they believed, the city would tear down the High Line and an opportunity for public space would be lost forever. (They were right. Less than two years later, the Giuliani Administration sided with the landowners and signed a demolition order for the High Line.)

A funny thing happened, though, once David and Hammond took up this project. It turned out—to their surprise and others’—that these two were uniquely equipped for a civic project of this magnitude and complexity. While they had no experience in leading an urban change effort, they had valuable and complementary skills. One could write well and knew some in New York’s social and philanthropic circles. The other was experienced in starting things, was at ease in asking people to do things (including giving money), and had a good sense of strategy. They were both quick learners, and each had an interest in art and design, which became important as the project moved forward.

It took three years of contacts, conversations, fundraising and strategic planning for David and Hammond to accomplish two things that ended the discussion phase and began the planning phase: First, they halted the demolition order with a lawsuit; second, they arrived at a workable solution for the High Line. You can view their workable solution online. It’s a 90-page document titled “Reclaiming the High Line,” researched by a nonprofit called the Design Trust for Public Space and written by David.

It’s an interesting document for three reasons. First, it’s beautifully designed. It had to be because it was aimed at multiple audiences: the political and planning communities that had such a big say in what would happen to the High Line; the community nearby, which at that time had barely any idea of the High Line’s potential; and possible donors who needed to understand the High Line’s vision.

Second, it’s modest in spelling out that vision. While it makes a strong case that the old freight line should not be torn down, used as a transit line, or turned into a commercial development (a long, skinny retail area, perhaps?), it doesn’t say it ought to be a park, either. It simply says its best use is as open space in a part of the city where there isn’t enough. In other words, the workable solution keeps its options open.

The third thing that’s interesting is who wrote the foreword: Michael Bloomberg, who by 2002 had succeeded Rudolph Giuliani as mayor. This gets to an important element in any change effort: luck. The High Line project was lucky in who got elected during its 10-year path from concept to ribbon-cutting, starting with the person in the mayor’s office.

Well, if a workable solution is at hand and a powerful new mayor wants it to succeed, that’s that, right? What else is there to do? The answer: The real work was just beginning. And this is my central message about the planning phase. Getting agreement on a workable solution is like getting everyone to agree on the design concept for a new house. Now comes the difficult, detailed work of hammering out costs and financing, drawing blueprints and mechanical plans, obtaining building permits, and bringing together a small army of independent contractors.

As David and Hammond explain in their book, “High Line: The Inside Story of New York City’s Park in the Sky,” even with the new mayor on their side, there was still a gauntlet of approvals to be run, from community planning boards (basically, neighborhood organizations that review developments) to the owners of the High Line (CSX, the railroad company) and the federal agency that approves transfers of railroad rights of way. And they had opposition: from landowners who had expected to build where the High Line stood, but also from residents who couldn’t see how the dark, peeling, scary elevated railroad could ever be anything but an eyesore. Finally, they realized a truth about government: that, even in a strong-mayor government such as New York has, the mayor doesn’t call all the shots. As Hammond writes:

(By late 2002) the Bloomberg Administration fully supported the High Line, but if they’d only endorsed it and done nothing else, the project would have died. Everything about the High Line was complex, and it had to pass through so many different agencies and departments. City government is like the human body: the head, which is the mayor’s office, may want to do something, but the body has a number of different parts that want to go their own way.

Everything hinged on three tasks that occupied much of the High Line’s planning phase: Coming up with a design for the park that would please politicians and neighbors and excite donors; dealing with the landowners’ objections; and figuring out how to pay for the construction and maintain this most unusual park in years to come.

If this doesn’t sound like exciting work, it wasn’t. This is the slog of civic projects, but it’s also why the planning phase is so important. Managing these details determines the success or failure of projects. And there were hundreds of details, from mapping the decision points and how to approach each of them to knitting together a coalition of supporters and funders. There were competing interests that had to be satisfied and intense politics. Oh, and they had to design a park unlike any in the world, and figure out how to pay for it.

What this phase requires from leaders are three things: the ability to plan (that’s why it’s called the planning phase), a mastery of detail (in an earlier posting, I called this the realm of “small-p politics”), and a willingness to ask for things. Throughout its development, David and Hammond asked people to do things for the High Line. Early on, they asked for information and advice (who owns the High Line, and how should we approach them?). Soon after, they asked for support and permission. In time, they asked for money. They started by asking for a small sums for printing costs and filing the lawsuit against the demolition. Eventually, they asked philanthropists and politicians for millions to pay for the park’s construction and maintenance. And they got it, in ways that surprised even them.

This brings us to the three elements of the planning phase that are in the map of community change: champions, narrative and strategy. I put them in the map as reminders. We’ve talked about one, strategy—that’s about mapping the decision points and making plans for each decision. This is the “inside game” of civic change, the political and bureaucrat checklist of approvals.

But there is always an “outside game” as well, and that’s where the narrative becomes critical because it speaks to citizens and potential supporters and donors. A narrative, of course, tells a story. It explains the need, why the need exists, the opportunity for addressing the need, how the solution was arrived at, and the future benefits of the change. Sometimes, the narrative has to change how people think about their community and its potential, something I call “reframing the community’s mind.”

And finally, there are the “champions.” Obviously, David and Hammond are the central figures of the High Line project. Without them, the freight line would be a memory and a remarkable asset squandered. But they aren’t the champions I have in mind; they’re the leaders and strategists. The champions are those whom David and Hammond asked for support who brought others along. Some were political champions who used their influence to win approval and gain government funding—people like Mayor Bloomberg, two successive city council presidents, New York’s senators and congressional representatives, and a host of people inside the bureaucracy.

There were also business and philanthropic champions, like media tycoon Barry Diller and fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg who lent their names, made major financial gifts themselves, and hosted fundraisers for the High Line. Finally, there were celebrity champions who helped raise money and call attention to the High Line. An early celebrity endorser was actor Kevin Bacon, whose father had been an urban planner. Another actor, Edward Norton, also had a family interest (his grandfather was the pioneering urban developer James Rouse). When he read about the High Line project in a magazine article, he tracked down David and Hammond and offered to help out. As you can see from this video about the High Line, made before its opening, what Norton brought was public attention, which is what stars do.

The final box in the planning phase is “the plan,” but that’s a little too simple. In all likelihood, it’s not a single plan but a host of plans: one describing the project’s feasibility in great detail for decision makers, one speaking to the public about its benefits, one setting out the financing (for decision makers and funders), and one describing the design (if it’s a physical project). There will likely be internal documents that serve as a kind of project flow chart, laying out the approval process and decision points, and what each approval will require, so you can marshal the right supporters. Finally, your project may need interim funding, to print materials, commission studies and seek expert advice. You’ll need a plan for getting that funding along the way.

As I said earlier, this isn’t glamorous work; it’s a slog. The amount of detailed work and its complexity will test civic leaders’ commitment and attention spans. There will be victories along the way, and it’s important to broadcast them to keep your supporters’ spirits high. “One of the keys to the High Line’s success,” Hammond writes, “was in always showing progress, even if it was a really small step.” And sometimes there are big steps, like the day in late 2004 when Josh David opened an envelope and found a check for $1 million inside, from a donor he and Hammond had courted.

But make no mistake: This is the period when obstacles are met and overcome—or not. Do the planning phase right, and the next one, the decision phase, will be a triumph. Do it poorly and your chances of success are about as good as winning the lottery: theoretically possible . . . but practically impossible.

Photo of the High Line by Katy Silberger licensed under Creative Commons.