In a series of postings, we’re exploring how conscious change happens in communities. If you haven’t read the first posting in this series, please take a moment to do so.

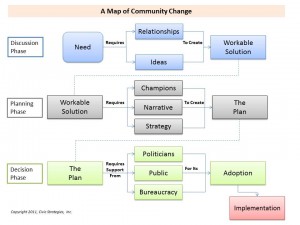

Let’s start at the top of the map, with the discussion phase. This is where change begins, with a leader recognizing a need and using her relationships, a set of ideas and a series of discussions to find a workable solution. But don’t let the casual-sounding name fool you. The discussion phase isn’t chit-chat; it’s a structured process involving different types of conversations with different groups, each a critical step in the change process. This phase ends with a decision about the solution to take forward.

You begin with the need—the community problem or opportunity that’s the reason for the change process. This sounds so commonsensical that I’d hesitate to mention it were it not for the fact that most community change efforts (and virtually all failed ones) begin with something else: a solution.

Look at the ideas floating around your city. If it’s anything like mine, you’ll find proposals for streetcars, parks, bike trails, changes in taxes, water conservation, redevelopment finance, road improvements, zoning regulations, and on and on. What do most of these ideas have in common? They’re solutions without context. Their proponents serve them up without first establishing the problem they’re intended to solve. As a result, they create a ripple of interest . . . before sinking out of sight.

Business consultant William Bridges knows why this doesn’t work. As he warns corporate executives:

Most managers and leaders put 10 percent of their energy into selling the problem and 90 percent into selling the solution to the problem. People aren’t in the market for solutions to problems they don’t see, acknowledge, and understand. They might even come up with a better solution than yours, and then you won’t have to sell it—it will be theirs.

Right on both points: If people don’t believe a problem exists, they’re not going to buy its solution. And when they do accept the need, they’ll often come up with good solutions on their own—which ends not with your leading people but marching with them. And that’s exactly where you want to be.

The keys to introducing a successful change process, then, are to convince citizens and decision makers of the need for change and, in time, facilitate a group of people who’ll arrive at a solution. Let’s take these in turn.

Begin with the need. It can be a problem (vacant properties in a neighborhood, say, or a declining local economy) or an opportunity (a local university that could have closer ties to the community). It can be a short-term problem (say, a spike in crime) or a long-term problem (domestic violence). You might start out with a solution in mind. Let’s say you’re concerned about obesity, and it seems to you that more sidewalks and playgrounds could go a long way toward solving it. If so, put aside your solution and concentrate on the problem.

This is harder than it seems. We were all rewarded in school for having the right answers, but in leading a change process it’s better to be the quiet kid in the back of the room than the one in the front row with his hand up. Why? Because many people eye change suspiciously. You may think you’re offering helpful ideas when you volunteer solutions, but some will see a hidden agenda. It’s better to say you don’t know the answer yet—and politely ask people for their thoughts.

And then there’s what William Bridges said: If you’re successful at getting people to accept the problem and think about it, they may come up with better solutions than you had anyway. So for both reasons—it lessens resistance and opens the door to other, perhaps more creative, ideas—it’s far better to sell the problem at first than to push a solution.

But how do you sell a problem effectively? I’ll write more about this in the future, but in general leaders must do four things to move people from awareness to action. They have to convince them that:

- The problem is a community problem; it’s not just a personal issue.

- It’s an important need, one that affects the community’s future.

- It is urgent; things will grow worse with delay.

- It’s possible do something about it; the community has the ability to solve the problem or significantly reduce it. It’s not hopeless or beyond reach.

When you convince people—decision makers and citizens—of these four things, something wonderful happens: People and resources are drawn to you. If offering solutions builds resistance, convincing people of needs does the opposite: It smooths the path of acceptance. Again, the trick is to build confidence that a solution can be found while not offering up a specific one.

The next step is to gather a group of people to talk about the need, discuss a range of possible solutions and agree on one to take forward. Who should be in this group? If you’ve done a good job of talking about the need—in small meetings with decision makers, in larger forums with citizens, perhaps through the news media and social media—then you know some who should be included. These are people who’ve responded to your call for action with support and resources. If you’ve spent time building relationships in the community (see “What Glengarry Glen Ross Teaches Us about Change“), you’ll know others who should be involved.

But you should also be strategic. You are assembling what John Kotter, the Harvard business professor and expert on corporate change, calls the “guiding coalition” for the change process. The coalition will change somewhat as you move through the planning and decision phases, but basically it is the group that will be the brains and muscle behind your initiative, the strategists and doers.

And who makes up a strong guiding coalition? Kotter suggests four types (which I’ve modified slightly for community change projects):

- People with expertise in the issue.

- Those with power in this area.

- People with credibility in the community.

- Leaders who’ve shown they can get things done.

For a change effort about obesity, then, the experts might be public health officials and perhaps those who run youth sports programs. Those with power might include school system officials, city parks officials and public-works officials. The other two types are harder to suggest, but you almost certainly know those in your community with a track record of getting things done and those whose judgment is respected. For the latter type, you might want to consider leaders in your city’s ethnic communities: If there are special problems with obesity among African-American or Latino youths, who can speak credibly for, and to, these families?

When you bring the coalition together, the initial goal to arrive at a workable solution (see “What Makes a Solution Workable?“). How do you manage such a thing? Well, there’s a great deal to learn about group facilitation—far more than I can cover in this posting—but three guidelines will serve you well:

- Be patient. You will almost certainly introduce people to one another, so allow time for members to talk and listen. Good decisions require trust and candor. You won’t get them in a single meeting or probably in several sessions . . . but you can in time.

- Start with the need and return to it frequently. The best way to begin a group’s work is with the need: a thorough discussion of what makes the problem a community concern, why it’s important and urgent, and why members believe it can be solved. As the group gets bogged down debating solutions, bring it back to the need. It will remind members of the importance of their work and encourage them to stick with it.

- Keep an eye on group dynamics. One dynamic to watch for is a rush to judgment by the experts or those with power. This shouldn’t be surprising. These are people who’ve been thinking about this problem for years. They may even have solutions they’ve promoted in the past that they’d like the group to endorse. You’ll need the others—those with credibility and leadership ability—to slow things down by asking questions, gently challenging assumptions and pushing for new answers. This is an important role but one that some are uncomfortable playing. So before the first meeting, you may want to ask one or two of the most confident leaders to be the questioners of assumptions.

One way to improve the group’s work is with some “market tests” along the way. With the group’s permission, take its tentative ideas and assumptions to decision makers and citizens, through private meetings, op-ed articles and forums. This has an obvious benefit: Before committing to a solution, the group needs to know what decision makers think, how citizens respond, and where the likely obstacles lay. Yes, it will slow the process, but that’s not necessarily bad. It will prevent a rush to judgment and allow members time to know each other better.

And, who knows? Someone you talk with might offer a better solution than the ones the group was considering.

Photo by Jason Diceman licensed under Creative Commons.