As I write this, America is in the middle of a fever dream over who should be the next president. Every four years, Americans endure an astonishing amount of foolishness from our politicians, and this election has already served up way more than its share. Sorry, I can’t fix America’s crazy electoral system. (Pray for us.) But I do have some experience in making thoughtful decisions about people running for mayor, city council, county commission, school board, and just about any other local elected position.

It involves pulling together a group that cares about local politics, thinking a bit about the offices up for election and what they demand, creating a fair process of evaluating the candidates for these offices, then creatively engaging voters in a conversation about what it takes to be a good officeholder. What the group creates, in effect, are job descriptions for elected officials. And that act alone is a big step forward—for the group and (depending on how effective it is at engaging the citizens) the voters as well. I know. I’ve seen this approach work in two different cities. It might work in your city, too.

I was launched into this sideline in 2001 when the Metro Atlanta Chamber of Commerce asked my help with one of its affiliate organizations, the Committee for a Better Atlanta, whose sole purpose was to evaluate candidates for local elected office. Most of the time, the Committee slumbered. It awakened for a few months every election cycle, interviewed candidates, announced its findings, then went back to sleep. In that period, it worked like a newspaper editorial board or the endorsement committee of a political interest group: sitting down with the candidates, listening to their ideas, asking about things of interest to the group, then announcing who should get the job.

But two things were different in 2001. First, the Metro Atlanta Chamber did not want the Committee for a Better Atlanta to be seen any longer as just another interest group. After all, the chamber represented the region’s entire business community, not just one self-interested industry. And the Committee’s makeup was broader even than the chamber’s, pulling in a number of other business groups. The result was a diverse coalition of organizations concerned about Atlanta’s future, with a particular interest in its economic well-being.

The second difference was the election itself. In 2001, Atlanta was in a crisis. The mayor, Bill Campbell, had been indicted and would, in time, be convicted and sent to prison. The city faced huge financial and infrastructure challenges, much of which did not interest Campbell. The chamber and the Committee’s leaders felt the city could not afford another corrupt or indifferent mayor. They wanted this round of endorsements to make a difference.

So they asked me: Did I have any ideas that could help the Committee with its work? I’ll spare you the details, but the first thing I suggested was that the Committee meet and agree on its purpose and how it wanted to work. The results: It wanted to influence the election, it wanted to evaluate candidates in the fairest way possible, and its members were open to doing things differently.

This was helpful because I thought the three were connected. The best way to influence the election in a positive way, I felt, was to be transparently fair. And the best ways of being fair were to evaluate the candidates in a different way and present the results in a different way.

Wouldn’t it be better, I asked, if the Committee didn’t just announce to voters whom they should vote for but rather began a conversation about what makes good elected officials? One of the Committee’s co-chairs eventually came up with the right analogy: Maybe we could evaluate candidates the way Consumer Reports rates automobiles.

Consumer Reports doesn’t endorse cars. It defines the attributes of a good car (reliability, safety, performance, comfort, fuel economy, and so on), then tells you how each model performed in each category. If you valued reliability above all else, you could compare the models just for that. If performance and comfort were your things, you could look just at those scores. Want to put all the attributes together? Consumer Reports offers an overall score.

If we could bring this approach to judging candidates, we decided, the Committee could accomplish all we were seeking. It could engage voters in thinking about what makes good candidates for local office. It could point them toward the good ones by offering its assessments. But it could do so in a way that would seem fairer, because . . . well, it was fairer. This new approach began by judging everyone by a set of reasonable criteria. If two candidates were close in their qualifications and positions, that would be clear. If a third was woefully inadequate, that would be obvious as well.

This seemed like a breakthrough, but this was actually the easier part of our new approach. We had an innovative form, but what would be its contents? If Consumer Reports thought safety, reliability, comfort, and fuel economy were the elements of a good car, what were the elements of a good candidate? So we went back to the group with this question: What do you value in an office seeker? In other words, if you were writing a job description for mayor and city council members, what would you include?

The answer that emerged was that most members looked for two things: political positions and personal qualities. That is, they wanted elected officials who did the right things (and their positions would tell you what they wanted to do). But they also wanted officeholders who could accomplish what they set out to do and do so in the right ways, which has to do with ability and character.

The positions weren’t that hard to figure out. Given the city’s problems and Campbell’s shortcomings, this group of business people was focused on better city management, infrastructure investments, public safety, and stronger government ethics.

But the personal qualities were more difficult to define. After much discussion, Committee members came up with three attributes:

- Does the candidate have a vision for the city and a personal vision of what she can accomplish in a four-year term?

- Does the candidate have a set of experiences and qualifications that could make her effective as an elected official?

- Could she actually accomplish the things she wants to do? In other words, once in office does she have the ability to implement the vision?

Once we knew the issues and qualities, what remained were mostly logistical questions. Among them:

- How could we phrase questions so candidates would answer them thoughtfully and candidly? And, specifically, which questions should we ask in person and which could be answered on questionnaires?

- How should we organize the in-person interviews? Should candidates be rated after each interview, or should the panel wait until all candidates were interviewed and then rate them as a group?

- What should we do about candidates who couldn’t or wouldn’t appear before the panel?

- Once the ratings were complete, how should we present the findings to the voters and explain our rating system?

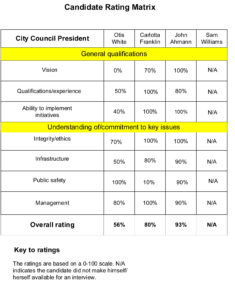

Finally, there was the rating scale, which touched off a lively debate. I thought it should be on a 1-to-10 scale or maybe 1-to-5, but Committee leaders felt strongly it should be a 1-to-100 scale, since that felt more like the grades people remembered from school. So that was that. And if a candidate didn’t show up? He got an N/A, which stands for “not available.”

How did it look in practice? Before we started the evaluation process, I offered the Committee a mock-up, using my name and the names of three chamber employees. Here’s how it looked.

We held the interviews at a hotel in downtown Atlanta. We did a training session with Committee members before the candidates arrived, including a mock evaluation in which one volunteer answered questions evasively and another completely so members could see the difference. Everyone who was a Committee member (and my recollection is that it was a big group, perhaps 40 or more) sat in on the interviews for mayor and city council president. Then we divided them into panels for the city council races. They filled in their evaluations after all the candidates in a race had been interviewed. For such an unfamiliar approach, it went surprisingly smoothly.

One reason was that we had spent a lot of time thinking about the division of questions between the questionnaires, which candidates filled out in advance, and the interviews. Our criteria was this: If the question might reveal the candidate’s ability to reason logically, we asked it in person. Everything else was asked on the questionnaires.

You could see the difference in two questions we asked about infrastructure. The first was asked on the questionnaire:

In your opinion, what are the three greatest infrastructure problems facing Atlanta over the next four years? Please rank them in terms of expense and urgency. (There was space for three—but not more than three—answers.)

In the interviews, we asked a second infrastructure question:

In the questionnaire, you identified the three greatest infrastructure problems facing Atlanta in the next four years. Taking a look at the one you ranked as most important, please tell us how you would address this infrastructure need—and how you would pay for it.

We knew the Committee for a Better Atlanta was made up of business people who had long experience in looking at resumes and then drilling down in interviews for a job seeker’s problem-solving abilities. So that became our guide: Let background and big ideas be spelled out on the questionnaires and let the “how” parts be explored in person. (Actually, I think this approach would work for almost any group.)

When we were finished with the interviews, which took place over two days, we had the candidate scores and a good story to tell about our process. Then we had to figure out how to present these things to the voters.

Today, this wouldn’t be much of a mystery. You’d create a cool-looking website, with the ability to compare the candidates and explore the issues. You would have a page about the process and how it worked. You might include videos of the interviews, along with the questionnaires and candidates’ answers. You’d have short bios and links to the candidates’ websites. You might have interactive features (build your ideal candidate!) and places for comments and questions. And, of course, you’d have a marketing campaign to catch the voters’ attention.

But this was 2001. The iPhone hadn’t been invented. Netflix wouldn’t start streaming movies for another six years. Many people had access to a slow version of the internet but not everyone. We decided, then, that a booklet was the best way to present the information, something that could be inserted into a newspaper a week before the election. Then we called a press conference on the steps of Atlanta city hall to announce our new approach to rating candidates. (Hey, this was the way things were done in simpler times.)

In the end, did it work? Did the Committee for a Better Atlanta really influence Atlanta’s 2001 elections in a positive way? Oddly enough, the chamber wasn’t as interested in this question as I was. And, in truth, there are limitations to knowing how much impact a single group’s efforts can have on an election.

I tried my hand at answering the question in two ways: First, anecdotally; then by doing a little math. I started by looking at whether there were any surprises in the endorsements. That is, whether the new approach had caused Committee members to look at the candidates in a different way. And I thought it had, at least for the two most high-profile positions, mayor and city council president.

In both cases, the Committee rankings had surprised me. The two who scored highest for mayor and city council president were Shirley Franklin and Cathy Woolard. Both were less familiar to business leaders than their rivals and generally viewed as less business friendly. So something in the process had caused this group to consider the candidates in a more open-minded way. That, I thought, was significant.

Then I looked at who won the election and how the Committee had ranked them. The candidates with the highest rankings for mayor and council president (Franklin and Woolard) had won their races. But what about the council members? As I told the Committee in a post-election analysis: “Congratulations. You now have the city council you wanted.” Of the 15 council districts, nine had contested races. Of those, seven went to the candidates rated highest by the Committee. And the other two districts were won by candidates ranked exceptional (90 on a 1-100 scale) or acceptable (73).

Together with the incumbents who did not have opposition (and, interestingly, they wanted to be rated as well; all of them showed up for interviews), the average score of the city council incumbents who took office in January 2002 was 89 out of 100. So, yes, this was the council the Committee had hoped to elect.

None of this proves causation, of course. I couldn’t say the Committee’s ratings caused a candidate to win her race or her opponent to lose. But it was possible. (Among other things, we knew that the Committee judgments influenced how business groups contributed to candidates.) At the very least, I thought, it reassured one influential group that it would have a much, much better city government than it had endured under Bill Campbell.

So, what has happened to the Committee for a Better Atlanta since 2001? There’s good news and bad. The good: It retained the Consumer Reports-style approach of grading candidates along issues and qualities. So if two rivals are close in their issue positions and abilities, that’s obvious from the ratings. If they’re miles apart, that’s apparent as well.

The bad: It no longer gives much detail about the ratings so you can’t tell where the candidates succeeded and where they came up short. That’s a shame because the ability to drill down on issues and qualities was, I thought, the key to engaging the voters about what makes a good officeholder.

And this conversation, conducted over time, can be more important than any single election. The aim should be to help citizens make consistently good choices in the voting booth. And the way to do that is to apply something we’ve learned in the business world: that it helps if you focus on the job before you consider the candidates. The critical first step in doing that, of course, is to write out a job description. Everything that follows should be about how the candidates measured up to that description. If we leave out the detail, I fear, then we’ve lost the job description.

Footnote: I got a second opportunity to run this experiment in judging candidates a few years later, when a civic group in Memphis (again, made up mostly of business people) contacted me. A critical county commission election was ahead, and the group’s leaders wanted to know if a process similar to the one we used in Atlanta might work in a city even more divided by race, class, and geography.

We went through the same process with the Memphis group (define the issues and qualities, judge the candidates by those standards, then engage the voters). The leaders there even chose a similar name (the Coalition for a Better Memphis). The issues were different, of course, but most of the qualities carried over.

One difference: This was a startup group, so Coalition members began a bit more skeptically than the Atlanta group, which had long practice in working together. But when they saw how deliberate and fair the evaluation process was, they were won over. So were the candidates as they learned about it.

And the results? The scores of the winning candidates in Memphis were even higher than the city council scores had been in Atlanta. So I told the group, in my post-election analysis, repeating what I had told the Committee in Atlanta: Congratulations. You now have the county commission you had hoped for.

And what has happened to the Coalition? I’m happy to report it’s still around and still rating candidates using the system we pioneered. I can’t say how effective it has been in maintaining its conversation with the voters.

Photo by WFIU Public Radio licensed under Creative Commons.